This article is part of TPM’s ongoing “Creating the Enemy Within” project, tracking the Trump administration’s efforts to crack down on dissent.

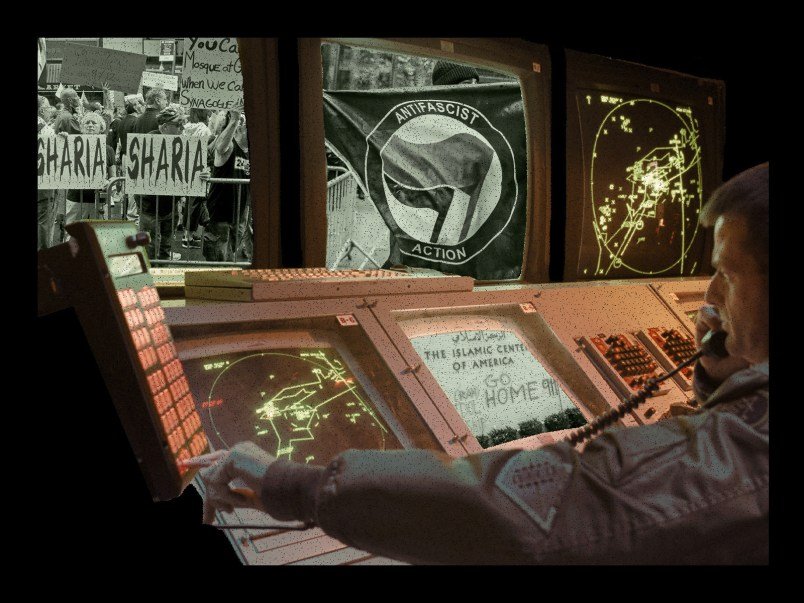

For years, conspiracy theorists, grifters, and would-be authoritarians in search of a useful internal crisis have howled about a supposed threat hell-bent on destroying the government and the American way of life: antifa.

The howling continues. What’s different now is that leading members of the chorus of “antifa” alarmists have left their gigs as right-wing YouTubers, social media influencers, presidential candidates, and staffers at fringe nonprofits. There, they could weave whatever reality they wanted: America could be in the grips of a Weather Underground-esque movement, beset by a national wave of antifa violence.

Now, some of these people are in the federal government. They’re demanding that the apparatus of federal law enforcement do what they couldn’t achieve on various podcasts, Truth Social posts, and video appearances: first define, and then dismantle, “antifa.” This sweeping campaign to criminalize an ideology is now using some of the biggest guns in federal law enforcement’s legal arsenal — terrorism charges — to quash dissent.

Next week, a Texas terrorism trial against what the Department of Justice has cast as an “antifa cell” begins. It will be the first time that the Trump administration has had to argue what it believes antifa to be in a criminal case. Prosecutors have brought material support for terrorism charges against eight people, and secured guilty pleas to the same from another seven. The defense argues that there was no terrorism and that the DOJ has overcharged the case because the defendants adhere to an ideology that the Trump administration dislikes, leading to guilty pleas over an incident that, the defendants contend, stemmed from a peaceful protest that went awry.

To make their case, prosecutors have turned to a group long known for spreading anti-Muslim conspiracy theories to provide them with an expert witness to define what antifa is supposed to be. That organization, the Center for Security Policy, has been designated by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a hate group. Its founder and former leader, Frank Gaffney, spent decades claiming that “creeping Sharia” was infecting American life. (Gaffney didn’t return an emailed request for comment.) In recent years, the Center for Security Policy has added countering the supposed antifa threat to its repertoire.

The problem, as scholars, former domestic terrorism prosecutors, and left-wing advocates will tell you, is that antifa does not exist as a coherent, organized group. There’s no organizational structure or national leaders to speak of; few people that the Trump administration officials lump into “antifa” would describe themselves as such. As a 2020 Congressional Research Service report put it, antifa members see themselves as “part of a protest tradition,” but the group itself “lacks a unifying organizational structure or detailed ideology.”

“It’s worth asking whether they’re struggling to define it or whether that’s part of the whole shtick.”

Mark Bray, Rutgers professor and author of “Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook”

Tom Brzozowski, who left a position as domestic terrorism counsel at the DOJ last year, took issue with the description laid out in a pair of memos targeting antifa that the White House issued in September. “They refer to it as a ‘network.’ I don’t really think that’s the best term for it,” he told TPM. “‘Individuals that effectively subscribe broadly to a common ideology or a common set of ideologies’ maybe is a better way to describe it.”

When Michael Glasheen, operations director for the FBI’s National Security Branch, called antifa “our primary concern right now” at a congressional hearing in December, Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-MS) asked him how many members the group had, where it exists, and other factual questions. “Well, that’s very fluid,” Glasheen replied.

In the Texas trial, prosecutors’ attempts to define “antifa” and the “cell” have already raised eyebrows. At a hearing in the case last year, a federal prosecutor suggested that antifa is primarily concerned with opposing the Trump administration. The federal prosecutor asked a testifying FBI agent if antifa is “really kind of an anti-President Trump and anti-ICE movement; is that right?”

“Yes,” the agent replied. “We’ve seen that rhetoric and terminology in many of their demonstrations.”

Islamism to Antifa

The Texas case revolves around a demonstration on the evening of July 4. A group of activists from the Dallas area converged on an ICE detention facility in Prairieland, Texas. They allegedly shot fireworks and graffitied nearby cars; prosecutors say one security camera was destroyed.

But what happened next escalated this incident from what the defendants have described as a raucous “noise demonstration” to, in the government’s telling, the activities of a supposed “antifa cell.”

A local police officer responded. One of the gathered demonstrators then allegedly shot him. The officer survived.

Though the initial charges were more bare-bones, focusing less on the ideology of the protesters and more on planning around the event, federal prosecutors began to describe the incident as the work of an “antifa cell” in October. The switch came days after the White House issued a series of memos directing law enforcement to dismantle antifa in the wake of Charlie Kirk’s killing. There’s no known link between antifa as the group that right-wing pundits imagine it to be and Kirk’s killing, except for one detail that the Trump administration initially seized on. One bullet was inscribed with “hey fascist, catch” and a series of video game commands — an apparent reference to the Helldivers 2 third-person shooter game. Though most experts say that the shooter’s motive appears more incoherent and extremely online than anything else, it prompted President Trump and Attorney General Pam Bondi to claim that the shooting was part of “antifa.”

That doesn’t solve the problem for Texas federal prosecutors, who will need to define, for jurors, what antifa is, where it comes from, and how it works.

For that, court filings show, they’re calling Kyle Shideler, the director and senior analyst for homeland security and counterterrorism at the Center for Security Policy.

Shideler declined to comment in a brief phone call with TPM, and didn’t respond to an emailed list of questions. The Center for Security Policy also did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Shideler spent much of his time before 2017 covering a different set of issues entirely: radical Islam and the terrorist threat that it posed. He worked for the Endowment for Middle East Truth, a pro-Israel nonprofit, before he began around 2014 to write for the Center for Security Policy, where Gaffney made a career out of spreading fears of “creeping Sharia” and a supposed plan for “Civilization Jihad”: a fantastical Islamic plot to take over the United States that was briefly cited by Ben Carson at a 2016 presidential debate.

“It’s shocking to me that that’s the best [expert] the government could find.”

Dr. Anne Speckhard, director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism at Georgetown University

Trump’s first term was more focused on Islamophobia, with banning travel from Muslim countries as a key campaign point. But as the term went on, he began to invoke “antifa” as a shadowy movement stoking violence around America to further left-wing goals. During that period, Gaffney also started drawing attention to antifa’s supposed presence in the United States. Shideler began to as well, positioning himself as an expert. And when Trump returned to office, his preoccupation with Islamic extremism faded in favor of his desire to root out “the enemy within.”

In one recent interview with right-wing activist Chris Rufo and far-right publisher Jonathan Keeperman, Shideler described antifa as groups of “autonomous Marxists” and “revolutionary leftists” operating under a “united front.” For Shideler, what’s required is a whole-of-government approach to dismantling antifa, as he laid out in the interview and in an article several days after Kirk’s death.

That description evokes a level of organization which apparently conflicts with what an FBI agent said during a probable cause hearing in the case. There, he described antifa as “loosely organized,” “a decentralized anarchist mindset,” and an “ideology.”

“It is an ideology that these people believe in, and those who self-identify as it practice this in a lot of aspects of their life,” he said.

That, in turn, raises deeply troubling questions. It suggests that FBI agents in the case may be regarding adherence to what they imagine as antifa as itself worthy of investigation, conflating belief or association with criminal conduct. For Shideler, “antifa” often seems broad enough to encompass a range of conduct, from peaceful protests to planned violence against law enforcement.

“Just because a network is decentralized and non-hierarchical does not mean that it’s not an organization for purposes of criminal or other statutes and that does not mean that they do not exist,” Shideler said on a podcast in October. He added that the “problem we have right now is that our federal law enforcement officers have not done that background work.”

Mark Bray, a Rutgers professor who has written extensively about antifa and fled to Spain last year after local right-wing activists targeted him for supposed ties to the group, told TPM that this vagueness over what antifa is allows for more leeway in pursuing it.

“It’s worth asking whether they’re struggling to define it or whether that’s part of the whole shtick,” he remarked. Bray told TPM that he had been retained by another defendant’s legal team in the Prairieland case as an expert witness on antifa.

Other experts in the case told TPM that they were surprised to see Shideler — or anyone affiliated with the Center for Security Policy — called as the government’s expert.

“It’s shocking to me that that’s the best government could find,” Dr. Anne Speckhard, a psychiatrist who studies terrorists and who is being called by the defense as another antifa expert witness, told TPM.