The Texas Senate passed new bounty hunter-style abortion legislation Wednesday night to quash mailed abortion pills, targeting a method that has slipped through the cracks of abortion bans and contributed to the slight rise in the total number of abortions since the Supreme Court decided Dobbs.

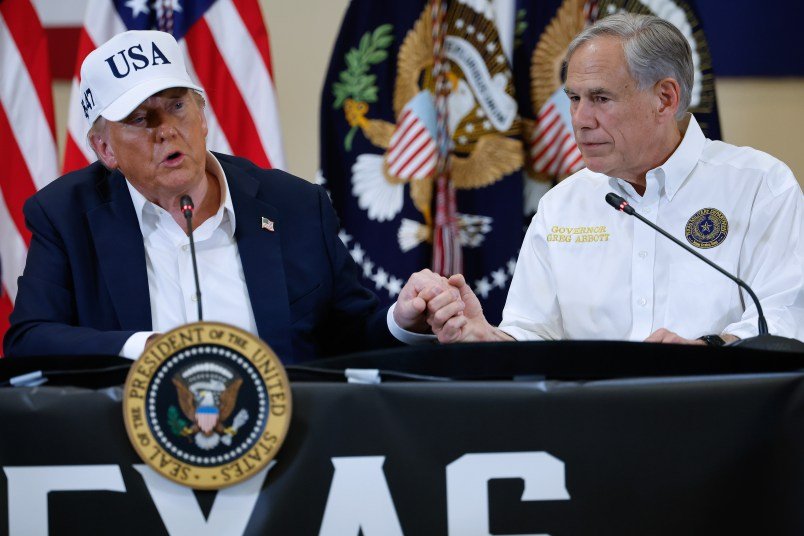

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R), staunchly anti-abortion, is expected to sign it.

The bill would allow people to sue the manufacturers, deliverers and providers of mailed abortion pills for damages. It sets up a long-predicted abortion showdown: red state abortion bans versus blue state shield laws. Many blue states passed such laws after Dobbs, specifically to protect providers and patients in their states from red state prosecution.

The case law here is thin and the central questions largely untested. How far can states’ laws extend out of their territory?

“Patients leaving the state to access care, get the procedure and come home is one thing,” Jessie Hill, associate dean and reproductive rights scholar at Case Western Reserve University School of Law, told TPM. “But when you’re sending pills into a state, you are reaching into that state in a sense.”

Texas’ thirst to prosecute blue state doctors has already reached the courts in a different case.

In late 2024, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) sued a New York doctor for allegedly prescribing abortion medication to a Texas resident (the medication was allegedly discovered by the Texas woman’s partner, whom she did not tell about her pregnancy). When the provider did not appear in court, under cover of New York’s shield law, Paxton sought a $100,000 penalty, filed in New York.

Acting Ulster County Clerk Taylor Bruck declined to file Paxton’s motion.

“In accordance with the New York State Shield Law, I have refused this filing and will refuse any similar filings that may come to our office,” he said.

Paxton pushed Bruck to reconsider in July; the clerk again declined.

“The rejection stands. Resubmitting the same materials does not alter the outcome,” he wrote in a press release. “While I’m not entirely sure how things work in Texas, here in New York, a rejection means the matter is closed.”

Texas’ new legislation, by design, will be difficult to preemptively challenge, as it’s enforced by ordinary citizens. A legal clash is likely only after someone is sued under it.

“They’re trying to provoke a fight over the Comstock Act,” Hill said, referencing an 1873 federal law banning the mailing of abortifacients that the anti-abortion movement has been eyeing to ban mailing the medication.

Texas has been increasingly citing the Comstock Act in other legal attacks on abortion access, including in its effort to join a red-state attack on mifepristone. That zombified case is the latest iteration of an effort that the unanimous Supreme Court rejected for lack of standing last June. It’s dragged on at U.S. District Court Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk’s court, where a random assortment of red states has tried to reinvigorate it under the infamously anti-abortion judge, despite the litigation having no jurisdictional ties to north Texas, where his courtroom is based. Texas is currently trying to remedy that problem, asking to join the case earlier this month.

The fight over medication abortion is the fundamental one that will shape the post-Dobbs world. The anti-abortion movement has been stunningly successful, even pre-Dobbs, in regulating surgical abortion out of existence in large swaths of the country. Medication abortion, though, which has steadily increased in popularity, has proven much harder to track and kill.

“It feels like we’re in a Prohibition-like era,” Hill said. “A ban doesn’t mean abortions stop happening.”

It’s no surprise that Texas, so often the laboratory for pushing the bounds of anti-abortion absolutism, is preparing to do battle against its fellow states to outlaw the abortion method, on the dependably friendly terrain of the Supreme Court.